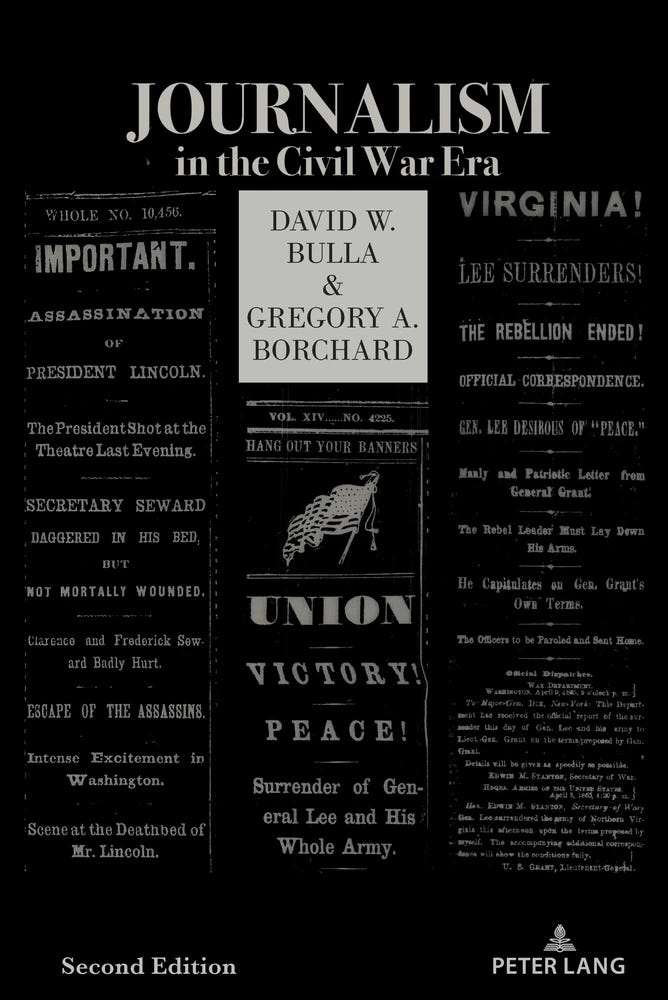

In light of all the chatter since 2021 about a second American Civil War and the role of the media in dividing and polarizing people, I had the opportunity to record a Zoom interview with two scholars of the period about their book, Journalism in the Civil War Era. I found their book to be revelatory.

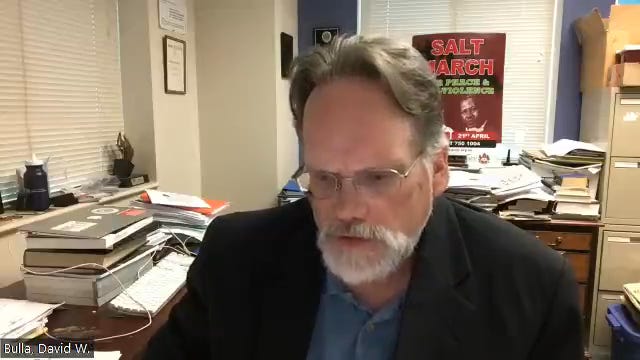

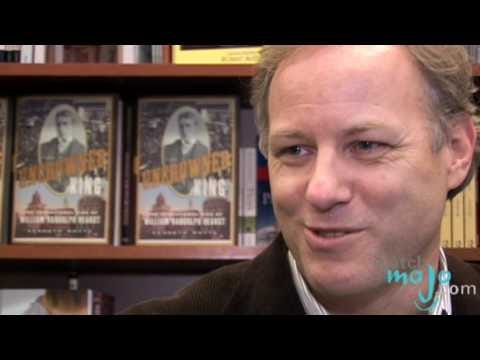

David Bulla is a professor of communication at Augusta University in Georgia, and Gregory Borchard is a professor of journalism and media studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Excerpts from the transcript (edited for brevity and clarity):

Buie: Several pundits and scholars have noted the similarity between media behavior today and in the run-up to the American Civil War and during it. So you guys are scholars of the period. You know a lot more than most of us. I have a two-part question for you.

What are the similarities and what are the differences?

Borchard: I tend to think of this as an apples-and-oranges scenario. But at the same time, apples and oranges are both fruit, right?

So there are some similarities here. The mediums clearly are different.

The primary source of information for Americans in the 1850s and 60s would have been the newspaper.

And not that many people read the newspaper anymore. We use primarily social media. And the politics are, in some ways, apples and oranges, too.

We're not exactly fighting over slavery or the restoration of the Union.

But the hyper-partisanship is certainly comparable, and the way it gets put into media and transmitted and communicated to the American public has been very comparable.

And on top of that, I do think Americans are funny people, you know, they tend to forget things very quickly, they have a short-term memory.

And yet, at the same time, everybody's conscious of the Civil War and what happened and why it happened, at least they think they have ideas as to why it happened.

So the more intense things get, apparently, the more people think about the Civil War as a precedent for what we're going through.

With the recent elections of 2016 and 2020, especially, people have been entertaining all the comparable events, whether it's the election outcomes or the insurrections, so-called.

And people write about this and amplify it through social media and all the rest.

Right now, there are people doing polling of policymakers and the American public. And there is, I think, an alarming number of people who think we are headed towards a civil war. In 2022, there were 31% of American voters who believed that a civil war, a second civil war would occur before 2030. So within this decade. And national security experts have also indicated that within the next 10 to 15 years, there's a 35% chance of occurring.

There's a much greater chance that it won't happen. But the fact that almost a third of those polled indicate they think it will, that in itself is significant.

All it takes is a handful of people to get a civil war started.

It doesn't take 95% or even 50%. It's just a handful of really partisan, hyper-partisan people to get the guns firing.

That's my take on it.

Bulla: I agree with a lot of what Greg said, and especially the hyper-partisan divide I think is the greatest similarity.

I'll just briefly talk about media differences….First of all, you had a news media in the United States in the 19th century that was developing incredibly fast throughout the whole century in a qualitative way that was really amazing.

On the other hand, now I believe that the news media is devolving. I don't think it's anywhere near as strong.

Jim and I grew up kind of together in North Carolina in the 1960s and 70s and I think many people in journalism would say that the 72-74 period with the Watergate coverage especially in The Washington Post but it's also in The New York Times and to a certain extent on the three legacy television networks was a high watermark

And since then, it has been devolving, especially the print media, and especially the local journalism industry has been devolving and has been replaced, as Greg said, by social media.

On the other hand, in the 19th century, you had this incredible development. We went from just maybe a few hundred newspapers at the beginning of the century to thousands and thousands by the end of the century and we became a hyper-literate society.

I'm not sure we're hyper-literate anymore. I think we're sort of, I don't want to say we're illiterate, but we're illiterate because all we want to read is the superficial….

Buie: What I found shocking in your book, to those of us who have hero-worshipped Abraham Lincoln, I viewed him as the savior of the American Republic. What I found shocking was that he repressed media rights and free speech, and he seemed to feel that some media outlets were actually treasonous and were, in Donald Trump's phrase, enemies of the people. Can you explain this? Is my hero not a hero?

Borchard: I can try. Yes and no. You have to try to put yourself in Lincoln’s shoes as best as possible. I know it's impossible to do that.

A little anecdote for you. Both Dave and I had a professor back in Florida Bertram Wyatt Brown. He was from a military background and we came into the class from a press perspective. He taught Civil War history. (When he lectured on how Lincoln came down on journalists), either Dave or I… tried to (defend the press). (Lincoln’s generals) were more upset than anybody with the publishers for disclosing Information (critical to the war effort).

Wyatt Brown's response was something along the lines of, you know, you journalists, you're all like, you think you're the most important people in the world, and the world revolves around you. And the only reason we have freedom is because of the newspapers. It's just not true.

And what he was trying to say, I think was, yeah, freedom of the press is a great thing. But it's no good if you don't have a nation or a country in which to practice it.

This was Lincoln's thinking. From all accounts, he needed to preserve the nation to maintain freedom.

Now on the flip side, there were plenty of publishers, including Horace Greeley, (who argued) the flip side. What good is your nation if people aren't free?

And they did anything and everything they could, in some cases, just to poke the dog with a stick. Their approach was to try to push the envelope, so to speak. They wanted to be able to publish for the sake of publishing.

But…(Lincoln did not take) an all-or-nothing approach. There was a back-and-forth between the administration and the press at the time.

And I think they both understood the complexity of the situation.

From Lincoln's standpoint, hey, if the North was going to win the war, if the Union was going to be maintained, he had to put a stop to some of the press leaks that were jeopardizing lives.

That was his thinking.

The bottom line was soldiers were dying in some cases because of the leaks of sensitive military information and you can't win that way….

And there are other folks involved.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was actually very critical in all this…(He) wanted to know who it was that published that stuff so he could prosecute them.

…Lofty ideals of the freedom of the press do sort of collapse under the weight of human life. You can defend Lincoln in that respect.

You can also look at him as quite possibly the biggest villain to ever hit the stage of American history. There are 670,000 people who died under his administration after all.

How do you explain that? We have to believe something good came out of it.

So that's why Lincoln I think to this day is considered a hero.

Bulla: …In my view, Lincoln is still definitely a hero, although all heroes need nuance and humanizing…. The Southern news media were certainly traitorous.

And Southern journalism suffered for at least 50 to 100 years after that and probably deserves to.

…In the North, with the Democratic press, and even some moderate Republican newspaper editors, were they traitorous? In some cases, I think they certainly were, especially a guy like Brick Pomeroy up in Wisconsin, who basically said it would be okay if somebody knocked off Lincoln. That kind of thinking just was wrong. I mean, it's criminal.

And he was extremely lucky that he was not prosecuted after Lincoln's assassination…..

Buie: Do you think that the suppression of newspapers and censorship were necessary to win the war? Dave?

Bulla: This is where I'm close to being as divided as you can be on all of this, which I think in a way is what you should expect when you're talking about civil war and civil war journalism.

I tend to doubt it. I think Lincoln overreached…(But) the whole idea of a libertarian approach to freedom of speech and freedom of the press during a civil war is problematic at best.

Buie: I just want to tell the audience the book is Journalism in the Civil War Era, by David Bulla and Greg Borchard. Click to learn more about the book.

Related:

50 Signs U.S. Is Moving Toward Civil War

The only way to avoid civil war is to recognize early and ominous developments and to take steps to ensure the potential for violence is not escalated but reduced. Opponents of abortion have long said that it’s the modern moral equivalent of slavery. Those who favor abortion rights think the Supreme Court Dobbs decision taking away a national constitutional right is morally equivalent to the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act which

Media's Profound Changes

In the second part of my conversation on Journalism in the Civil War Era with the authors, David Bulla and Greg Borchard, I pointed out that some analysts have suggested that the media today, with so much fragmentation, is more like the no- holds-barred 19th century media than it is to the mid-to-late 20th century media, where you had just three to five…

The Birth of Yellow Journalism in the 1890s

The 24-hour news cycle — intense competition between cable television networks and online outlets for public attention — has led to a burgeoning “angertainment” industry — so-called news packaged in ways to generate outrage and division rather than insight.

Share this post