In the second part of my conversation on Journalism in the Civil War Era with the authors, David Bulla and Greg Borchard, I pointed out that some analysts have suggested that the media today, with so much fragmentation, is more like the no- holds-barred 19th century media than it is to the mid-to-late 20th century media, where you had just three to five major TV network news outlets, CBS, ABC, NBC, PBS, and then a little later, CNN and Fox.

We had all these gatekeepers then, but in the 19th century, there weren't many gatekeepers, and on the internet there are no gatekeepers. So do you agree with that?

Borchard: It's hard. As much as we'd like to be able to come up with nice storylines and narratives that connect all the dots, there's always an alternative way of looking at things. I am partial and sympathetic to the idea that we are living in a hyper-partisan age. And if that's the case, we're probably closer to the sort of political climate that took place right after the American Revolution and not necessarily before the Civil War itself.

We had two major opposing parties at the time, with Federalists and Anti-Federalists and they engaged in all-out warfare against one another. And yes, you do see that today.

In fact, Eric Burns, a former commentator, put together a book (Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism) that more or less described our current press climate as similar to the dark ages of journalism as it's been called where everybody goes to war against each other on two major sides, and there's very little common ground in between.

Yeah, I can see that. But at the same time, there are so many different kinds of sources that people are getting their information from today that at a certain point, the comparison breaks down, whether it's social media or television, or even movies, or you name it.

It's not necessarily newspapers, but we do get some of the same narratives that were developed in the newspaper industry.

So it is hard to come up with a generalization that works.

I mean, for convenience sake, I do think that the politics of today are pretty comparable to the politics of the dark ages of journalism, as it's called.

But the journalism itself, I'm not so sure. The mediums are pretty dramatically different, put it that way.

Bulla: We were taught, at least at the University of in Florida, a theory called the two-step flow where what you described, Jim, is what kind of happened in the middle and latter part of the 20th century where essentially the New York Times and CBS especially sort of set the (nation’s) agenda, along with the president and some other powerful figures, sometimes in government, sometimes in the business arena and cultural arenas. And then it kind of spread down a network that would include our local newspapers and our local radio stations.

And those gatekeepers that Greg was describing played essential roles in deciding what we should digest and what we didn't even get exposed to.

That's gone. I mean, it's just absolutely gone.

We're all now our own gatekeepers in a sense, although not really, because what we do is we end up subscribing to the echo chamber of our choice, or we just, if we're agnostic in a sense, we just ignore the whole system.

I think in some ways getting away from the two-step flow was a really, really good thing. It had the potential to make us more independent thinkers when the internet really started to explode in the late 1990s, early 2000s.

We were, I was, at least when I went to Indiana to get my master's in journalism, I was incredibly optimistic….I'm like, oh, wow, we can create all these new audiences…

I didn't expect this vast wasteland and that's what we have again. We have this muck and mire…

There's just too much choice out there and it doesn't necessarily read to the best outcomes for our society, especially a society that wants to remain, I think, a democracy.

A democracy really does need good information and somebody needs to lead it…

Buie: I then asked Drs. Bulla and Borchard to describe the chapters of their book, beginning with the first chapter, on Schuyler Colfax, who was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the House of Representatives from 1863 to 1869. More from Wikipedia.

Bulla: …Colfax to me is really one of the sort of luminaries of this time. It's not necessarily that he was a great journalist. I think he was a good one. But he represents what journalism kind of was in many ways. He was a journalist and a politician.

Horace Greeley (a newspaper editor, publisher, founder of The New York Tribune who ran unsuccessfully for president in 1872)…wanted to be president so bad that after the Civil War, he switched parties. He helped found the Republican Party and he switched to the Democrats to try to get elected, to try to beat Grant, who was a war hero, who probably really didn't care which party he belonged to in some ways….

But anyway, Colfax was not unusual at all for this period of time. Being a politician and being a journalist was like something that worked together. Leadership came from both.

I think everybody at that time realized that. And it was not only seen as acceptable, it was almost seen, I think, as you were almost an elite part of society or being noble by both leading as a politician and as a journalist.

And I think Colfax had a heck of a run until he became vice president when it all fell apart because of one scandal.

He certainly didn't hurt Lincoln at all. He was one of those Republican editors in northern Indiana and in the northern states whose good work as a journalist in South Bend, Indiana, certainly paved the way for Lincoln to upset Seward….

This is about the time that that convention happened in 1860 in the Wigwam in Chicago.

I mean, literally, there is no way, if you look at it, Lincoln should have won that nomination, and he does.

I mean, that's another kind of the cool thing about all of this whole era.

Lincoln is the most unexpected president we've ever had. He's the most uneducated.

I don't care what Bill Clinton says because Bill Clinton had a pretty good education after all he went to Oxford ultimately.

Lincoln had no real formal education. He was absolutely self-educated.

He become president and he believed as an ideal that I think is a great American ideal, that you could get somewhere just by how hard you worked and how much you applied your shrewdness, you know. And that's a great ideal.

And, you know, but if he hadn't had people like Colfax and Samuel Bowles up in Massachusetts supporting him, it doesn't happen.

Because Seward, you know, he had really the whole establishment behind him.

And that's a complicated story that you should read Greg's book on Greeley to get the background on.

But this is a very interesting man, Colfax, a very, you know, rise and fall guy, too, because at the end of his political career, he was he was an outcast.

Buie: Greg, can you talk a little bit about New York journalism in the 1860 election?

Borchard: It's another one of those stories that's full of drama and intrigue, especially in Chicago during the nomination process. William Seward had been picked early to be the nominee for the Republicans, and it was almost a slam dunk. People went almost as a formality, but little did anybody know that Lincoln and Greeley had other plans.

Lincoln set up the convention in Chicago intentionally. It was strategically located geographically and all the rest. He had his press insiders and lobbyists work in the convention floor and on top of it, what truly nobody saw coming was Greeley had it out for Seward.

And it's one of those strange sort of cringy moments of history where you're wondering what was that guy thinking?

He had a grudge against Seward for not promoting his, Greeley's, own political career. Greeley had always wanted to be an elected official and he blamed Seward and Weed, Thurlow Weed, for not advancing him politically.

So in his mind, he (Greeley) was going to Chicago to make sure that Seward didn't get nominated out of revenge. kind of a spiteful, petty thing to do, but it worked.

Somehow Greeley wound up as a delegate from Oregon, of all places, not New York, his home state, but Oregon. And he wound up circulating on the convention floor and whispering into the ears of delegates from Indiana and Pennsylvania, especially that if they elected or nominated Seward, he'd just be looking out for New York and they needed another candidate to represent their interests.

And as it turned out, almost by accident, the process evolved. And after the first vote, Seward didn't have enough. Lincoln got his operatives out on the floor, and he rose up in the polling. And by the fourth round of polling, Lincoln overtook Seward.

Nobody saw this coming, except for maybe Lincoln. And the rest is history, so to speak.

Now, as it turns out, Lincoln was not popularly liked. I think that's one of the great misconceptions of history.

This guy got into office with only 39% of the popular vote, and nobody in the South was even able to vote for the guy. He went in with support from people in the Midwest and the Northeast and editors who were Republican editors, not Democrat or Copperhead or any of that.

You know, hindsight is a brilliant thing. We can all use it to our advantage. But I don't think anybody truly anticipated that Lincoln was going to be president. In some respects, it may have been an accident.

Buie: A wonderful accident that saved us. David, can you talk about how the press would spin the news, how they would spin various battles. It wasn't necessarily accurate.

Bulla: Well, you know, I talk about three battles that happened kind of in the middle of the war…what's interesting is that the newspapers, North and South…would spin what was going on. And really, they didn't know….

News was much slower, but they felt like, especially if they had a daily newspaper, they had to say something every day, something new if possible to keep readers interested…So spin was really important and made a huge impact on the readers, I think.

Borchard: Sometimes they had to play it out over days, weeks, even months before they figured out who had won. And certainly in (Horace Greeley’s NY Tribune), you would see these epic descriptions of so-and-so pulling ahead in Ohio and individualized coverage of precincts and states and all the rest.

It sounded like it was straight out of Homer, some of these descriptions that they came up with. It's pretty wild.

Buie: Greg, can you talk a bit more about Horace Greeley and his New York Tribune?

Borchard: Greeley's a tough nut to crack, so to speak. Everybody's tried to figure out this guy from a bunch of different angles. And for me, that's the beauty.

You can't really nail them down to one particular perspective. He was a very complicated guy. He had all sorts of different political leanings.

He was a Whig, a Republican, even a Democrat, a liberal Republican, you name it.

He was sort of the conduit for all these different ideas that were percolating around the country at the time. And for me, that's a virtue.

I thought, you know, to this day, this guy set the model for the way the press should operate. His whole approach was, if you've got a good idea, I'll publish you.

And he wasn't necessarily choosy about whether or not it was something he agreed with or disagreed with.

He certainly did have his own partisan beliefs. But when it came to the Tribune itself, it was filled with content from all over the world even.

He would publish authors from England… Charles Dickens would contribute, Nathaniel Hawthorne, you name it, Edgar Allan Poe, they were all there.

And his idea of and for the press was to use it as an instrument to build society up. Boy, it'd be nice if everybody in the business took that approach.

But what you really see more commonly is people use the press, whether it's newspaper or anything else to make money. And yeah, you got to make money to stay in the business.

But on the flip side, you had James Gordon Bennett (founder, editor and publisher of the New York Herald), who would publish anything as long as it made money and that anything sometimes included sex and violence and scandal and the gossip and all the sleaze and all the rest.

So in an ironic way, I suppose Greeley was extraordinary in as much as yeah, he published anything like everybody else, but his mission was to build up society with these ideas.

Buie: Did he make a lot of money in doing that or was it more altruistic would you say?

Borchard: Yeah I think it was altruistic. He was kind of a rags-to-riches story.

I try to put him in the same category as Horatio Alger's characters but not really.

Like he went from nothing, he was born into poverty essentially, to becoming probably the most widely known publisher of his day, maybe even through today.

But he didn't die rich. He died insane in an asylum, tragically enough. But by that time, he'd given a lot of his fortunes away. Some of it was invested poorly, but he just didn't have a lot of money when he died….

I think Greeley is one of the great Americans of all time. I hope people don't forget about him throughout the rest of the history.

Bulla: I always say that, Jim, that if you had a Mount Rushmore of journalism, I might have to put Greeley in the Washington place. He was that important.

You know, the next guy might be Edward R. Murrow, but Greeley really transcends almost everybody else, I think.

Buie: David, can you talk a little bit about how the technology changed journalism practice?

Bulla: I'll make a quick comparison. I believe in the last 30 years, two things have changed our whole world….(the Internet and the IPhone)…

The same thing happened in the 19th century with two pieces of technology. One was the ever-improving printing press.

Really, for almost 400 years, the printing press had pretty much been the same as what Gutenberg had invented in the mid-15th century. But in the middle of the 19th century, especially a fellow named Richard March Hoe, H-O-E, was constantly improved the printing press…And you went from having…a few hundred newspapers a week to being able to make tens of thousands in a few hours every night. And so daily newspapers really took off, especially especially in New York and other urban areas.

But then the other technological invention, I still think the most important technological invention, really, in the history of communication. And that's the telegraph, because the telegraph ends the distance-time problem (in the news) that you have when you have to walk it, ship it, you know, use a horse to get it somewhere or whatever. It took time. And now, literally instantaneously, you could transmit information.

And really, the devices we have today, the cell phone is not any different, or a television, or a radio, or whatever. They're all instantaneous communication.

And it really dramatically changes everything about American journalism.

Information from where, as long as you had wires strung up, information could be gotten immediately.

It really starts about with the Mexican War. By the time we get to the Civil War, it's absolutely crucial, especially for newspapers like Greeley's and Bennett's in New York, where they were really industrial strength by then.

They had a reporting corps and an editorial corps. And they even had a corps that did the beginnings of images in newspapers, usually maps is all it was.

But you start to head toward what will be in the 20th century visual age.

It's just an incredible watershed moment in the history of mankind.

I really am that adamant about it. I'm not the only one.

Jim Carey, who's one of the most famous qualitative historians of mass communication, also said that the telegraph was the most important invention ever in communication.

(snip)

Buie: Okay, we've got just about a minute left. Do you guys want to make any closing statements?

Borchard: The Civil War won't go away. I kind of wish it would. So we could put to rest some of the issues that people died over. But it's still very much part of our consciousness.

And it will be as long as Americans are Americans, coming in from all over the world with very different backgrounds and identities.

I think we don't have to relive the past, but we're going to be battling some of the issues that are all part of the American fabric, as long as America is America.

Bulla: That's profound. I can't say anything quite that profound, but I will say that as Shelby Foote said about the war itself, it was a hell of a mess. Even journalistically as to what you should and shouldn't do.

I mean, you began it with Lincoln. And, you know, should he have been censoring these newspapers or professing these newspapers? So it was a mess.

And yet it was a it was a moment where some kind of clarity came out of it, at least temporarily, I think.

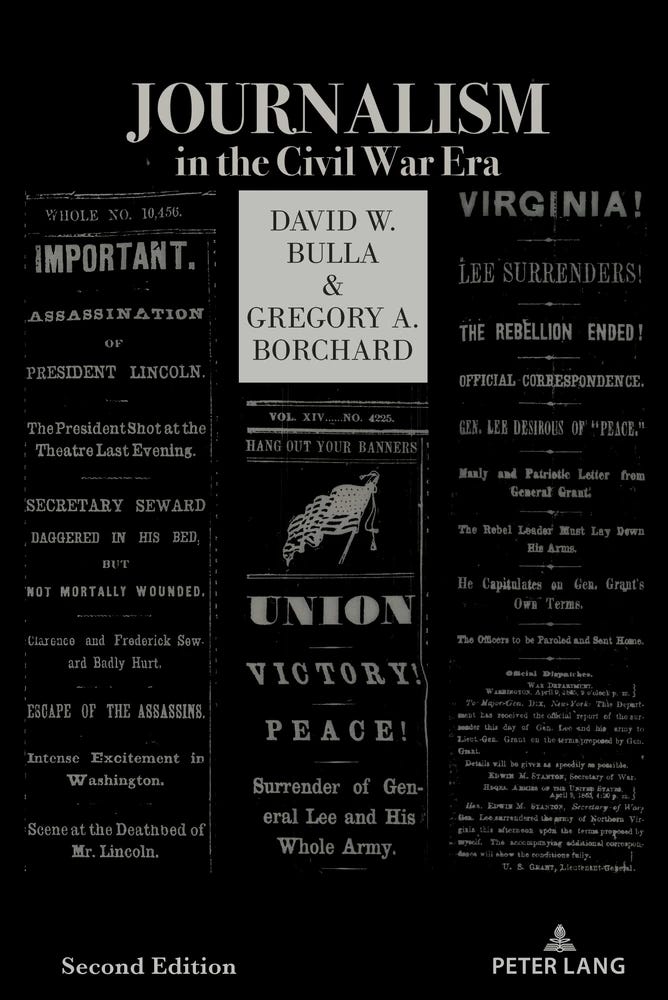

Buie: Yeah. OK, this is the book. I recommend it highly. It's a revelation. Get the book. Journalism in the Civil War Era by David Bulla and Greg Borchard.

(This transcript was edited for brevity and clarity.)

Part One of this conversation is here. Hyper-Partisan Media Contributed to the U.S. Civil War. Comparison to the 2020s.

The Birth of Yellow Journalism in the 1890s

The 24-hour news cycle — intense competition between cable television networks and online outlets for public attention — has led to a burgeoning “angertainment” industry — so-called news packaged in ways to generate outrage and division rather than insight.